Designing for Archives, FOWD 2013

— Oct 2013

I had the privilege of attending this year’s Future of Web Design conference in New York. Thanks to Ian Murphy and Michelle Barker for running a great conference and for inviting me. I noticed that there was a lot of focus on craft, both on the side of design and on technology. So I wanted to step back, and talk about the dusty corners of websites—personal, cultural, commercial—their archives. It’s first-and-foremost a content problem, that I hope will see more attention from design and technology. Here is what I said:

Hello. My name is Allen. Despite the title of this talk, I’m not a trained historian, I’m not a trained archivist. Like you, I make things for the web. These days I work as a digital designer at the New York Times.

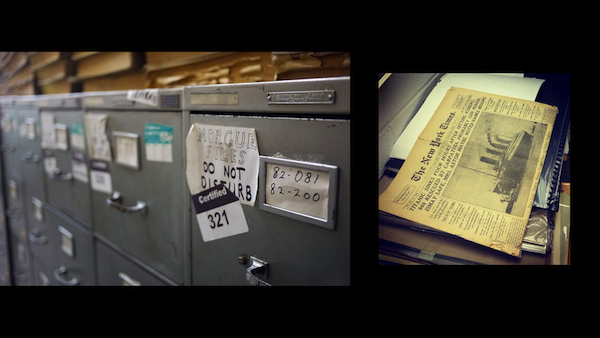

The first month that I started working there, I went on a tour of the paper’s morgue. And I found this: this was the paper’s front page the morning of the sinking of the unsinkable Titanic.

The file cabinets kept here contain newsprint clippings and photographs, sorted by topic and time. The man who takes care of this place, Jeff Roth, said that everything here once lived in the same building as the reporters. The reporters would send requests for past clippings on, say, someone who was running for office or for someone who died and needed an obituary, and the morgue would send back a runner with a file folder. This was part of their research and after they were done, the reporters sent the clips back down.

Many newspapers and magazines kept similar archives, but most of them have been cleaned out, and dismantled, and thrown away because they require so much space and money to maintain. This morgue is one of the few that still remain open today. The morgue lives in a separate building now, down the street from where I go to work every day.

I don’t know how much this morgue gets used today.

So, designing for archives. What do we think of when we talk about archives? Do you think of places like the morgue? Does your mind conjure up images of deep underground vaults, with dusty shelves with even dustier manuscripts? Or perhaps you think of the tombs of the pharaohs, hidden away in the pyramids? These are places that have been forgotten, either because they fell out of people’s everyday lives or because the people to which these things did hold meaning for are now gone.

The Internet was designed to be redundant and resilient. Sure, we still sometimes lose data, and sometimes lots of it. But generally, when unsinkable things sink, it tends to make headlines and people pay attention enough to try and stop it.

What happens to the past far more often is far more difficult to guard against.

Let me ask you this. How many of you remember what happened the last time you were on Instagram? How many of you, without checking your phone, even remember the last photo you took?

When you scroll through your Instagram feed, it lets you teleport instantly, to California, to Greece, Vietnam, South Africa, and back, to see things happening right now in five different countries. We can collapse so much space into a moment in time, but we aren’t as good at the opposite, at getting a sense of this other dimension, of what you are doing and you’ve done in the past. And so what happens far more often to the past is that we simply forget. It slips our mind so easily, because for us it was just things that happened, they don’t have any meaning or weight, and when enough time has passed that they slip from not just our short-term memory, but our long-term memory, that information becomes lost.

In other words, the question is about designing for amnesia. How do we design time machines?

So how does short-term memory work right now on web pages? You, the user, will typically see some recent activity on your profile page, and it gets shown as a reverse-chron feed of small, discrete entries. Now, you probably never look at it—I sure don’t—but I don’t find that very surprising. I mean, it would be a little like if you were talking and you asked me what I did yesterday, and I said—

- I woke up at 8:15.

- Then I took a shower.

- Then I got dressed.

- Then I walked the dog.

- Then I found a tennis ball on the sidewalk.

- Then I threw the ball.

- Then the dog chased after it, into the street.

- Then the dog almost got run over.

- and so on…

—well, I wouldn’t blame you for never again asking me how my day was.

The reason these activity updates are so short is that we’ve gotten really really good at atomizing the creation and posting of things to the web. Less often now do you think of putting up a blog post, or posting a photo album—more often you’re posting a tweet, and a single picture on Instagram, and a quick comment on Facebook.

But we can think of units of creation as separate from units of reflection. They can be separated. When personal blogs were where you posted long, substantial updates, you didn’t have to understand this distinction, because you were writing a post about traveling to Argentina and it would be just one cohesive update. But now, with people adding all these small morsels of things, as they go: some tweets about your flight there, Instagram photos of the sunsets, and Facebook comments about where you should go. When you look back, you’re going to have to forage around a little before the complete picture forms in your mind.

This atomization of creation is another topic for another day, but I think it’s mostly a good thing, it just means that we now have to start thinking very deeply about what the units of meaning are to a person.

See these two dinner plates? The plate on the right is the typical size in France, and the one on the left is typical in the U.S. In a study where they gave Americans food served on the smaller plate, they ate less and described themselves just as satisfied as when they had the plate size they were used to and ate larger portions.

There are of course cultural and psychological factors at play here—most people eat whatever’s on their first plate, then think about whether they want seconds, there’s unspoken cultural politeness about finishing what you’re served, etc—but the key thing remains that the size of the dinner plate acts as a “handle” for controlling how much you consume.

The typical activity feed is a bit like…not having a plate. You have no sense of how much you’re supposed to eat, and everything’s in these pea-sized morsels, they all look the same, and each one isn’t very satisfying on its own, so either you’re left hungry because you got frustrated and stopped, or you eat and eat and eat too much and now you feel bloated and are disgusted about yourself.

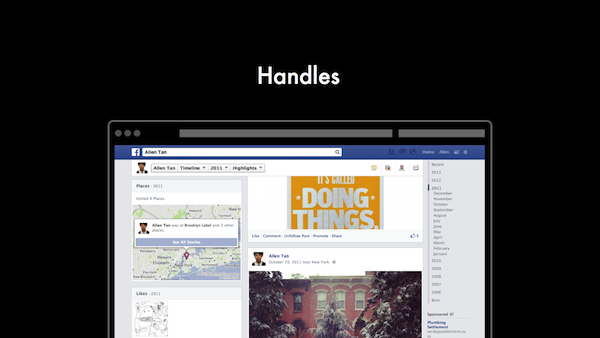

But, ok, some things online do have handles. Facebook has handles, for example, by collapsing your personal timeline into discrete years. This is a useful high-level method of organizing your activity, because not only does this give you a few things (but not an overwhelming number!) to navigate and filter by, it also gives you a sense of the whole. It lets you wrap your arms around this mass of information.

So you have years, and you can open each year up and navigate by month, and little discrete pieces of activity like adding a new friend gets bundled up together. This is all rather quite advanced, and is a clever way to make use of time, and it’s perhaps the most you can do without asking users to explicitly provide information like an event or a period of time.

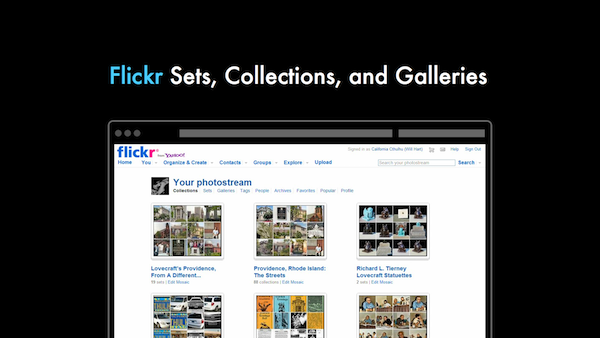

Now, I think we’ve been riding on this white horse of simplicity for a while now and we tend to bias automatic = good! and user input = too much effort = bad! But, remember Flickr? Flickr was the master of getting users to explicitly provide information. It was one of the sites that made the concept of tags famous, but they gave users many other tools to organize their photos. They gave users sets – sets are you think of as a regular photo album, they hold a group of photos. They gave users collections—collections group sets and other collections together. They gave users galleries—and the only rule with galleries is that you can only have 18 photos in a gallery, and the photos have to be from other users, they couldn’t be your own photos. Because the idea was for you to go curate and distill Flickr, this great mass of photos, into something that shows a specific perspective or framing.

Did users use these? They did! They didn’t mind the effort, they created them and shared them around and commented on them. These tools acted as handles for people’s photos. Flickr let you share any of those units publicly or privately. This was so flexible and powerful. So I could keep my photo stream completely private, and just for myself, and then I could create a set of photos of museums and the High Line that I took while visiting New York and I could share that set with my art class, and then I could create a collection that contained the High Line photos and maybe add some photos of the Cooper archive and share that to my design friends. It encouraged users to revisit their existing body of work over and over again, to think about it, and derive new meaning from it by letting them manipulate it.

Here’s another thing that bugs me: activity feeds organize items by reverse-chronological order. And this seems like the obvious thing to do, right? Reverse-chron makes sense both from a computer’s point of view, because it’s an easy way to sort things, and because it’s supposed to be “neutral”.

But when we humans look back at things that have happened in our past, we do not simply see this:

If we look at the history of, say, a Github issue, we’d talk about it like this: Sam found a bug, and then Martha chimed in to confirm it and suggested it might be related to a similar issue, and then after an extended discussion with Sarah and Vicky, Vicky submitted a patch that fixed it.

Right? We use sequence, we use cause and effect, to explain what happened. We created these atoms and we put them online, but once they’re online they’re no longer our own—they also take on their own life.

Their own history. Their own journeys.

By the way, this is v.1 Mixel, which was about composing fragments of images you found on the web into collages. What I loved about it was that someone looking at your collage could take any image in it and use it in their own composition. And you get this amazing view, if you select an image, of all the collages it was a part of.

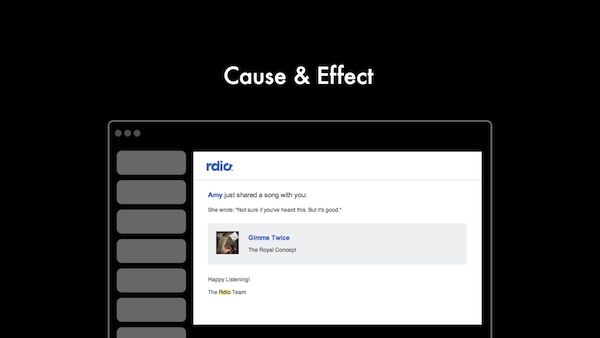

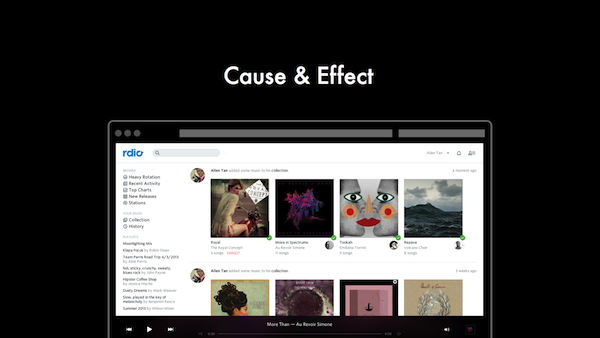

As another simple example, Rdio could make a deduction that if—

- a friend recommends a song to you, and

- you listen to it, and

- you add it to your collection

—they are separate events to a computer, yes, they can happen across distant points in time, and therefore it might show these items very far apart on someone’s activity feed. But they’re clearly tied to one another, and can be presented together. If I were looking back on my history, I’d want to see this relationship of events.

We can imagine and automatically capture some of these sequences when they happen, but they’re simply starting points. We could be wrong, in which case users should be able to correct what happened. And, like Flickr has demonstrated, if users are given the room to tell more complicated stories than we can anticipate, they will. We are giving them tools for storytelling.

Of course, we already have many places to tell stories. We post tweets, we post on Instagram, we blog. We already have places where we tell stories. So one way to answer the questions of How do we make the past relevant to us today? How do we let more people see them? is to be increasingly more visible on the platforms that people are on.

Here are three projects, and they’re similar in many ways. They all take something that’s very abstract and condense it into a form that travels with me and my social network. It’s where I already am.

Dronestagram is an art project by James Bridle, who’s from the UK, and for this project he keeps a running log of every drone strike that gets reported by the US military. On Instagram, he posts the satellite view of the area where the strike happened, photo filter applied and all, along with a description of the strike in the caption. And this is compelling because we don’t yet know how to wrap our minds around drone strikes. Unless you’re constantly checking news about drones, you don’t really have a sense of how often they happen. But a couple times a day, I pull out my phone and check Instagram. And usually what I see are photos from my friends. But once in a while, sandwiched in-between two photos is a satellite map with a sobering caption. You get something different through this sort of intermittent, embedded transmission than you do from reading an article about drone warfare in The New York Times whenever you remember to. If you remember to.

The political and practical possibilities of drone strikes are the consequence of invisible, distancing technologies, and a technologically-disengaged media and society. Foreign wars and foreign bodies have always counted for less, but the technology that was supposed to bring us closer together is used to obscure and obfuscate. We use military technologies like GPS and Kinect for work and play; they continue to be used militarily to maim and kill, ever further away and ever less visibly.

Yet at the same time we are attempting to build a 1:1 map of the world through satellite and surveillance technologies, that does allow us to see these landscapes, should we choose to go there. These technologies are not just for “organising” information, they are also for revealing it, for telling us something new about the world around us, rendering it more clearly.

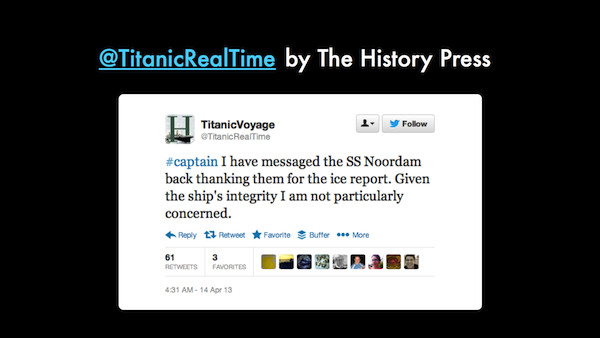

A similar project was undertaken on Twitter by The History Press for the 101st anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. It tweeted hypothetical bits and pieces based on research material, both text and photos, for an entire month leading up to the sinking, as well as its immediate aftermath. And while the drone project happens very slowly—at the pace of life and political reality—with no real narrative, the Titanic tweets are entirely narrative. Even before you begin following the account, you know how this ends. And yet, many of the early tweets are very light and silly. It’s funny, because they actually fit quite well in your timeline.

And yet, on the phone throughout the day, on the train, in line at the grocery store, at dinner, in bed late at night, you see these tweets as water starts to fill the Titanic. The rest of your timeline is still going on, life goes on, as if the world, your world that’s halfway in the present and halfway in the early 1900s, isn’t falling apart into the icy sea.

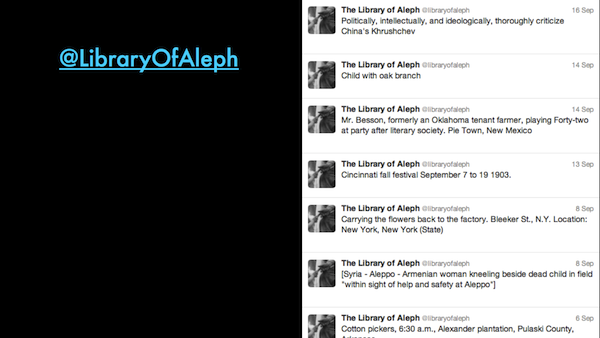

And third, is a Twitter account called the Library of Aleph. Its author goes through the Library of Congress and posts funny or interesting captions—no link to the photo, just the caption. It sits in the middle of a continuum between Dronestagram and the Titanic tweets, in terms of storytelling. It sort of spontaneously found a story. I don’t think the person who made this account had any particular “objective” for it—he was just tweeting interesting captions he was stumbling across in the archives. But the night of July 13, the night of the Zimmerman ruling, in the middle of all the anger and frustration that was coming out in waves and waves online, this account began tweeting these captions from history:

Martin Luther King, Jr., pulls up cross that was burned on lawn of his home, as his son stands next to him, Atlanta, Georgia

Execution of the thirty-eight Sioux Indians, at Mankato, Minnesota, December, 26, 1862

Japanese merchant posts sale sign in preparation for evacuation as small son looks on

Lynching of MacManus

Lynching, Sikeston, Mo.

Contrabands coming into camp in consequence of the proclamation

A group of “contrabands”

The ghetto, Chicago, Ill.

The Ghetto, New York, N.Y.

Human rights hot air balloon

Bombed wreckage of Bell Street Baptist Church

Group of students, some holding a Confederate flag in the air, protest the arrival of James Meredith at the University of Mississippi

Ex-slave with a long memory, Alabama

Rosa Washington, ex-slave, El Paso

The public swimming pool has been changed into a “private pool” in order to remain segregated

Unidentified young African American soldier in Union uniform

Nashville police officer wielding nightstick holds African American youth at bay during a civil rights march in Nashville, Tennessee

Alabama state troopers using tear gas and clubs against African Americans and others during the Selma to Montgomery march

African American woman being carried to police patrol wagon during demonstration in Brooklyn, New York

This kept going. It went through the night, and on to the next day, every 20, 30 minutes, relentless, an angry vigil, and not only did that hold meaning for people, that created new meaning, it was an act of renewal, this dusty “stuff” from the turn of the century met people’s anger. It told them, This is not new, it has happened before. It told them, You are not alone in this.

The Library of Aleph’s tweetstream the day after the verdict of George Zimmeran’s trial was announced was a relentless account of the history of African-Americans, from slavery through Jim Crow through the Civil Rights Movement. The person who created The Library of Aleph hadn’t created it for this purpose—it was really an account he put together to tweet out some of the interesting images he was finding without cluttering up his main account. But in his anger after the verdict, it became a platform for remembering and reliving our past.

I bring it up here because of this paradox: what makes the tweets so powerful is that they are disconnected from the material object they’re referencing. They’re just captions. We might gloss over images but I think we pause over these. What are we reading? Who wrote the captions? What does it mean to choose these words to describe these images?

These are tiny time machines. You are in the present, you are always in the present, because you were born in this decade and this century. But these time machines open a little portal to a specific time, just big enough to fit you. It is a ladder to the past. It feels more real, because it is embedded in the networks you use every day as part of your life. And you see these stories being told, or construct your own stories from what you’re seeing, stories from a long time ago being told anew.

We don’t need to design dusty shelves, and figure out how to make them matter. This is why they matter, why the past matters: because they coexist with us in the present, they’re not things we should put in a tidy box and forget about, because they are part of the stories we tell today, they are lenses that are personal and often political and they help us understand what’s going on now. All this stuff online—the things that real people put time into making and that real people look at—this stuff is our heritage. Let’s protect it better.

Thank you.

A few things that didn’t make it into my talk:

One, the Lively Morgue exists as a digital incarnation of the morgue, and embodies a lot of what I want archives to be. I actually had that as my last slide, but pulled it because that just felt insufferably smug. (Not that I’m always above that.)

Two, I was going to make a joke about the NSA being the best archive we’re going to get, but couldn’t think of anything to say that Aaron Straupe Cope didn’t already say.

Three, it’s funny how quickly the Archive Team has gone from a rogue band of internet misfits to a fixture of what we automatically think of when a site goes down.

Four, there were threads of how archives can embrace randomness in surfacing things, in collaborative + multi-session searching, and notes on Jefferson Bailey’s piece on respect des fonds that I wish I had the time and smarts to explore further.

Five, as Alexis Madrigal notes, the NYPL Labs team is fan-fucking-tastic.